The Dip — Seth Godin | Summary & notes

My thoughts 💭

The Dip brings an idea that goes against “common knowledge.” You often hear people say that you need to persist and never quit to be successful (whatever success means). Those who quit fail.

Instead, Godin suggests that the true competitive advantage lies not in blindly persevering but in knowing when to quit and when to stick. He then tries to explain how to do that.

Another relevant theme is the need to become the best in the world. Keep in mind that “world” is a flexible concept. It doesn’t necessarily mean the whole world.

The book is tiny, and it probably could’ve been even tinier, considering that some ideas are repeated. It’s worth at least a quick read if you’re interested in learning a strategy to deal with work (and life?) or want a take different than the usual “just persevere, and you’ll make it.”

Summary & notes 📓

A famous quote from Vince Lombardi goes like this:

Winners never quit and quitters never win

Actually, that’s not true. Winners frequently quit: they quit the right things at the right time.

More in general, you’ll have a competitive advantage if you can persevere more than others when it’s worth it but rapidly quit when it’s not.

Being the best in the world

In many areas in life, the winner takes (close to) all. Those who rank first have a vastly superior advantage over the rest. Even when compared to who ranked just below.

This happens because we’re used to looking for the best. We want the best restaurant in the city we’re visiting, the best person to hire, the best doctor for our condition.

And not only does the winner take almost all, but the places on the podium are hyper-limited. Why? Because most of the people quit way before getting close to it.

What does best in the world mean?

The definition of best in the world is not to be taken in an absolute sense, but it can mean best in a particular world.

An Italian software company based in Rome may want the best developer… within its reach, that can write mobile apps, that is willing to live in Rome, and that asks for a reasonable salary.

Thanks to the Internet, the world can now expand and shrink at the same time. It expands because you can access anything. It shrinks because more and more sub-categories are born. The goal, then, becomes to position yourself at the top of one of these micro-markets.

3 curves

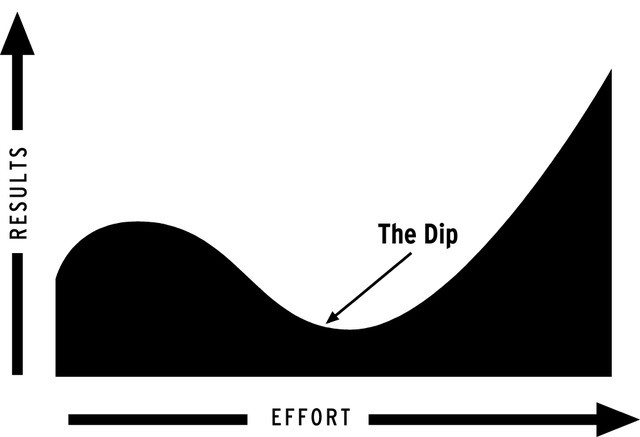

Curve 1: Dip

You start something new: it’s fun, and progressing is easy. Then, a long stagnating phase begins. That’s the Dip. Overcoming this stage makes the difference between amateurs and experts. It acts as a filter blocking those who don’t work hard enough.

Curve 2: the cul-de-sac

Aka, the dead end. You work, you put in the effort, but nothing changes. You don’t progress; there’s just stagnation. When you realize you’re in a cul-de-sac, you need to run away.

Curve 3: the cliff

Bonus curve that represents results that get better and better until there’s an abrupt fall.

(Negative) example: cigarettes. The more you smoke, the more you’re addicted, and the more difficult stopping becomes. In the end, they’ll probably kill you.

This curve rarely applies to careers. Chances are you’re on one of the other two.

In things worth doing, there’s almost always a Dip. The Dip causes scarcity, and scarcity, in turn, has value. If you realize you’re in a Dip, then you need to persevere. It is the opportunity to excel.

Moreover, if you realize that you’re venturing into an area with a Dip that you cannot or don’t want to overcome, it’s better to quit before starting.

If you realize you’re on a different curve, quit.

Many, confronted with a Dip, will diversify when they should exploit it instead. They become mediocre at many things instead of excellent at one.

Quitting as a long-term strategy

Often, people quit a Dip because they only consider the short term. A kid doesn’t drop out of karate because he thoroughly weighed the long-term benefits but because continuing is painful. The coach yells at them, and the training is strenuous.

The short-term pain has a disproportionate impact on our choices. So it’s essential to learn to become aware of this behavior and base our choices on the long term.

Nobody quits a marathon when they’re almost at the end. The bulk of the people give up when they can’t even see the finish line: in the Dip.

Quitting, instead, is a strategy for the long term. When you quit deliberately, you put aside the current tactic (that is not working) and direct your energies toward something else. The long-term goals don’t change even if you change your strategy to get there.

When you’re thinking about quitting, you need to be sure you’re thinking straight. Some questions you can ask yourself to get clarity:

Am I panicking? You don’t want to quit in this case because it wouldn’t be a rational choice. If you’re panicking, wait.

Who am I trying to influence? It’s common to be thinking of quitting because you’re not able to convince someone. E.g., your boss or the potential customers.

- If you’re trying to influence a single person, then persisting for too long won’t help.

- It’s different if you’re trying to influence a market. A market is made of multiple people, and many of them don’t even know who you are yet. It could be worth it to persist.

What measurable progress am I making? To succeed, you have to be able to progress, even if little by little. If there’s progress, it could be worth persisting.

Before starting something, it’s worth writing down the circumstances under which you would quit. Define your quitting strategy. It helps you think straight in case you face those circumstances.